21st Nov 2012 - 10th Dec 2012

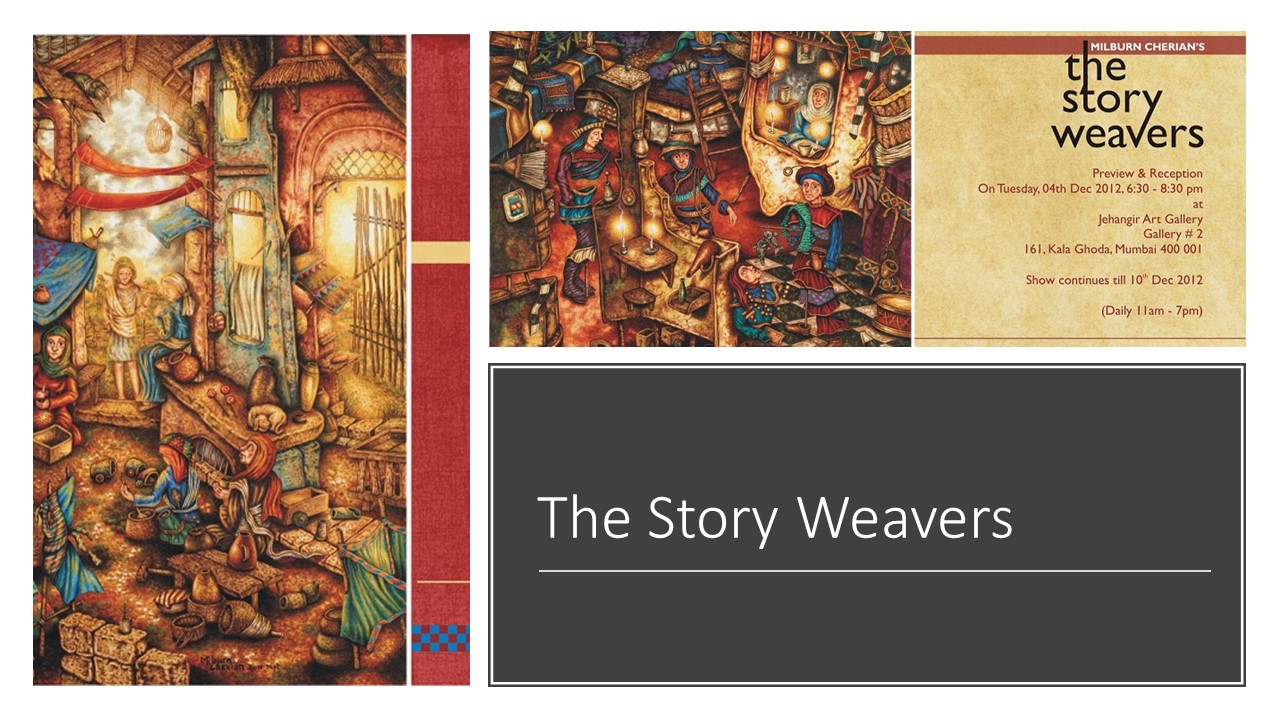

The Story Weavers-Milburn Cherian

Milburn Cherian

The Story Weavers

There is a place where the story weavers live. Here, everything has a different perspective with layers of transparency. Milburn Cherian’s works build surreal narratives of life with context to relationships, religion, carnival and daily life, bringing to light the importance of the existence of the smallest details. These miniature aspects and elements create a labyrinth of stories that weave themselves into each painting, while toiling for detail.

The bold colours, slanting buildings and defiant perspectives in Milburn’s paintings hark back to references from Peter Brueghel, Dali and German expressionism, where realism was rejected to uncover the deeper truth. The distortion of colour schemes breaks fixed notions and ideas we have developed to look at the world around us. The infinitesimal details that the artist implements makes one rethink time, relook at situations and the magnitude of the facets of living.

Where are the faithful; signifies the divisions in the church, where the conflicts of belief are causing the breakdown of religious institutions. The Christian belief of suffering as a path to salvation is bared through Jesus heals the lepers and the praying saint in The Lonely Way; which is also an aspect of personal choice. Hatter’s Party sets the tone for the artist’s engagement with carnival humour, while referring to C. S. Lewis’ references of Christian faith in Alice in Wonderland.

The mask, a recurring motif in Milburn’s work, celebrates the carnival and happier moments of life. ...But, how many of these moments are real? Are they only masked happiness? The saddest are the ones who laugh the loudest. Living in the Flesh and The Quarrel After; unmask the carnival to explore the essence of the sadness of the spirit that is otherwise phased by the short-lived happier moments. Milburn’s shift to a brighter colour scheme in her new works enhances this carnival aspect, but also displaces perspective, thereby creating a world that might appear to be distorted to the viewer, while on closer inspection reveals situations. It could be the aftermath of a wedding argument or the awareness of practised behaviour at a restaurant or carnival, as compared to the daily unsheltered rituals of behaviour in the comfort zone of a house; which reveal the levels of distortion in what appears to be a perfect perception.

One is lost within the walls one builds around them to create an allusion of the perfect situations. In these narrative cities, there are no walls. Everything is open for all to accept or reject incidents and experiences, which cannot be avoided in our daily lives. What one tries to do is mask them. The Barmaid, has all the elements one would typically see in a restaurant – from the pretence of being invisible through the mask in the forefront, to the man discreetly sitting at the edge of the painting being a peoples’ observer. Through her works, Milburn explores these rituals of daily life and the importance of the mundane – whether it is the Gamblers on the Roof or a lady by the window with a candle.

In the twenty-first century, a time where a candle is not of much use, it takes on the metaphor of hope. There is an aura and a source of outside light in Milburn’s works that establish hope, but also suggest the fire of purification; of going through hell to reach heaven. In Vain in Glory, the Wrath of God and Where Are the Faithful; the element of light that illuminates the paintings from within, imbibe a faith in reformed hope and promises.

In an attempt to unravel the complications of the world, the artist also includes personal nuances in her paintings, which connect her to clarify the details she toils for. Her dog at the table assists in the recipe of the improvising narratives in Playtime, while her parrot in The Big Kite, observes a clown shuffling his fortune.

By including elements of her private life in her works, Milburn creates a narrative bond with her works. Questioning the reason for fame and fortune, there are signs of suffering and downfall indicated by the cards – be it the gamblers’ playing cards or the clown’s tarot cards. Staircases, which signify ambition, are broken to create one level of understanding. The brown bandaged beings, suggest the cycle of life; of the eternal, supernatural beings, unravelling their bandages of truth.

In this gathering, there is an individuality to each face and character. On close observation, one will notice faces recurring in various paintings, but with a difference in character; signifying rebirth and an after-life, which the artist strongly believes in. Drawing from religious references, there are elements of faith and hope that appear in the form of various symbols of loss and hope.

These faces that delve further into the detail of the paintings appear to give a larger perspective from the detailed narrative; but what they actually do is reveal characters from this Golden City. Each face is a process of thinking further for the artist.

Maintaining the chastity of a child’s mind and intentions, the artist ensures that every child in her works is satisfied even during a period of grief or argument. The concentration on defining a character for the future roles that he will take up is an insight into the artist’s thought process of creating the details that keep one engaged with a work for a period of time. This is only to come back to realise the details and narrative, which had been missed earlier. Every viewer will re-live an experience to continuously weave endless narratives to perfection.